Filed under: Investing

What happened to the so-called Fed model? Although it was never actually endorsed by the Federal Reserve, the idea of comparing the 10-year Treasury yield and the earnings yield (earnings divided by price) on the S&P 500 has become a standard valuation tool for many investors. Moreover, for investors in SPDR S&P 500 or the iShares Core S&P 500 , a view on the value and future direction of the indexes is a critical part of investing. So how useful is the model, and what can investors learn from it?

Introducing the Fed model

As usual with valuation methodologies, there is no end of disagreement over which input factors to use. For reference, the earnings used in the following charts is as-reported, rather than adjusted. All of the raw data used comes from Noble prize winning economist Robert Shiller's website at Yale.

The basic theoretical idea behind the model is simple. An investor faced with buying bonds or equities might choose between a 10-year U.S. Treasury yielding, say 5%, or buying an equity with an earnings yield (earnings/price) of 5%. Roughly speaking, when the Treasury yield is below that of equities then it makes sense to buy equities, and vice versa.

The following chart compares the long-term performance of these two variables. As a rough guide, when the earnings yield (in red) is above the 10-year Treasury yield (in blue) then equity markets are seen to be cheap and vice versa.

Clik here to view.

Source: Robert Shiller Home Page.

Yes, you are reading the chart correctly! The model is implying that the S&P 500 is a screaming buy right now. So does that mean that equity investors should just pile into index ETFs and enjoy the ride upward?

The answer depends on how much you trust the model.

A false friend

The model became popular in the '80s and '90s because it appeared to provide a very useful way to judge the future direction of the S&P 500. In fact, plotting the 10-year yield (x-axis) against the S&P 500 P/E ratio (y-axis) and performing a regression analysis on the data produces a remarkable result.

The best-fit trendline in the chart generates an equation with a coefficient of determination, or R^2, of 0.83; a result which indicates a very strong relationship. In plain English, the equation (rounded up) of y=0.98x-1.5 means that for a 10-year yield of, say 5%, the S&P 500 earnings yield should be equal to 0.98*5-0.015=4.9%. Since the earnings yield is the inverse of the P/E ratio, this implies a P/E ratio of around 20 times.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

Source: Robert Shiller, author's analysis.

It's not hard to see why this metric became popular, because from 1980-2000 it appears to offer a failsafe way of investing in bonds or equities!

However, Foolish readers will note from the first chart that the relationship seems to break down after the year 2000. In fact, from 2003-2013 there is only one period where equities where not "cheap." That's 2009 when earnings (and therefore the earnings yield) collapsed during the recession.

Three explanations

There are many ways to interpret the relative cheapness of equities to bonds right now, or rather to interpret what the market is interpreting on the issue.

One approach suggests that bond yields are being artificially held down by massive injections of liquidity by the Federal Reserve. Therefore, equity investors may be saying that they don't really believe that equities are relatively cheap, because either interest rates will inevitably go up in a few years or earnings will fall in the future. Alternatively, both events could happen concurrently. For example, a collapse of confidence in lending to the U.S. could lead to Treasury yields rising, with damaging effects on corporate growth. However, if equity investors think that interest rates will go up, then why not just short bonds via something like the iPath US Treasury 10-year Bear ETN

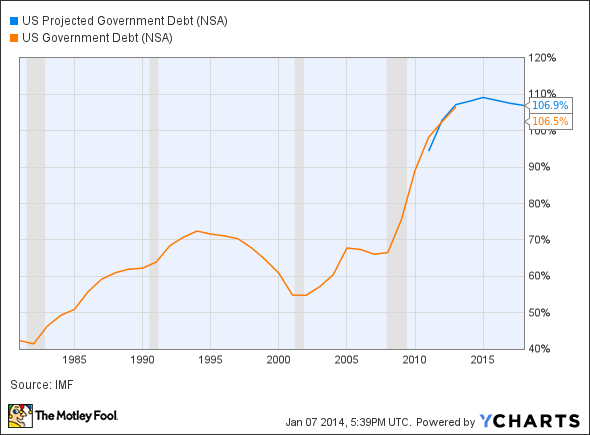

Another explanation is that investors are afraid of a cataclysmic event in the future, and don't wish to hold equities. Indeed, every recent global recession seems to have been deeper than the last. Moreover, the U.S. public debt situation is such that the U.S. (and the global economy) could face a severe and lasting depression if another recession takes place in the next few years.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

US Projected Government Debt data by YCharts

The third explanation is that asset classes' valuations tend to be the product of a combination of fundamentals and waves of enthusiasm that come in to the sector. It was equities in the late '90s, then property in the early 2000s, then oil and commodities, then it was gold, and now it's emerging market bonds.

The bottom line

Unfortunately, the Fed model doesn't provide a catch-all solution to asset class allocation. Any valuation method needs to be put into the context of the overall investment environment, and while it's easy to argue that the Fed model works under "steady state" conditions (such as between 1980-2000) it's a lot harder to predict when those conditions will come about again. Investing just isn't that simple.

So what's hot for 2014?

There's a huge difference between a good stock, and a stock that can make you rich. The Motley Fool's chief investment officer has selected his No. 1 stock for 2014, and it's one of those stocks that could make you rich. You can find out which stock it is in the special free report: "The Motley Fool's Top Stock for 2014." Just click here to access the report and find out the name of this under-the-radar company.

The article Whatever Happened to the Fed Model? originally appeared on Fool.com.

Lee Samaha has no position in any stocks mentioned. The Motley Fool has no position in any of the stocks mentioned. Try any of our Foolish newsletter services free for 30 days. We Fools may not all hold the same opinions, but we all believe that considering a diverse range of insights makes us better investors. The Motley Fool has a disclosure policy.Copyright © 1995 - 2014 The Motley Fool, LLC. All rights reserved. The Motley Fool has a disclosure policy.

Read | Permalink | Email this | Linking Blogs | Comments